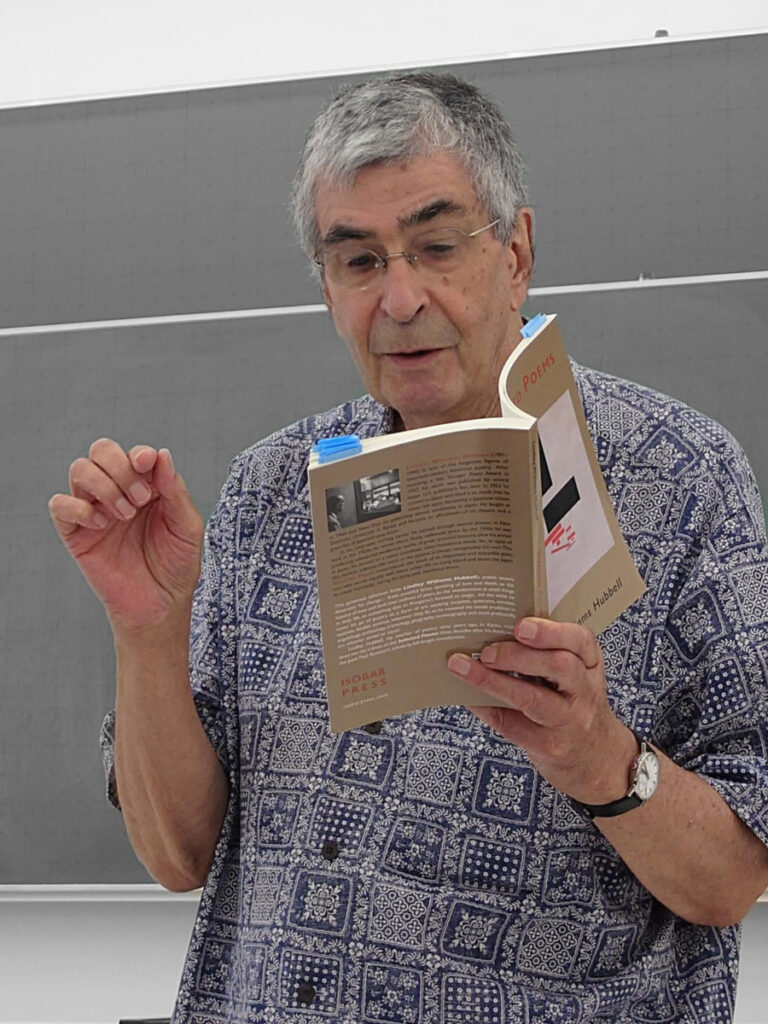

On Sunday July 13, at Ryukoku University’s Omiya campus, Paul Rossiter gave a talk about Lindley Williams Hubbell, a poet he considers to be unfairly neglected and worthy of much greater recognition.

Rossiter is himself a poet and the founder of Isobar Press, which recently published a handsome edition of Hubbell’s selected poems. He started his talk by using extracts from his own scholarly 38-page introduction to this volume to familiarise us with Hubbell. Hubbell’s mother had a passion for the theatre and often took him to see local productions of Shakespeare. Hubbell must have been profoundly influenced by this, because he said that he started reading Shakespeare at the age of eight, and by the age of ten, had not only read all of the plays, but memorised them too.

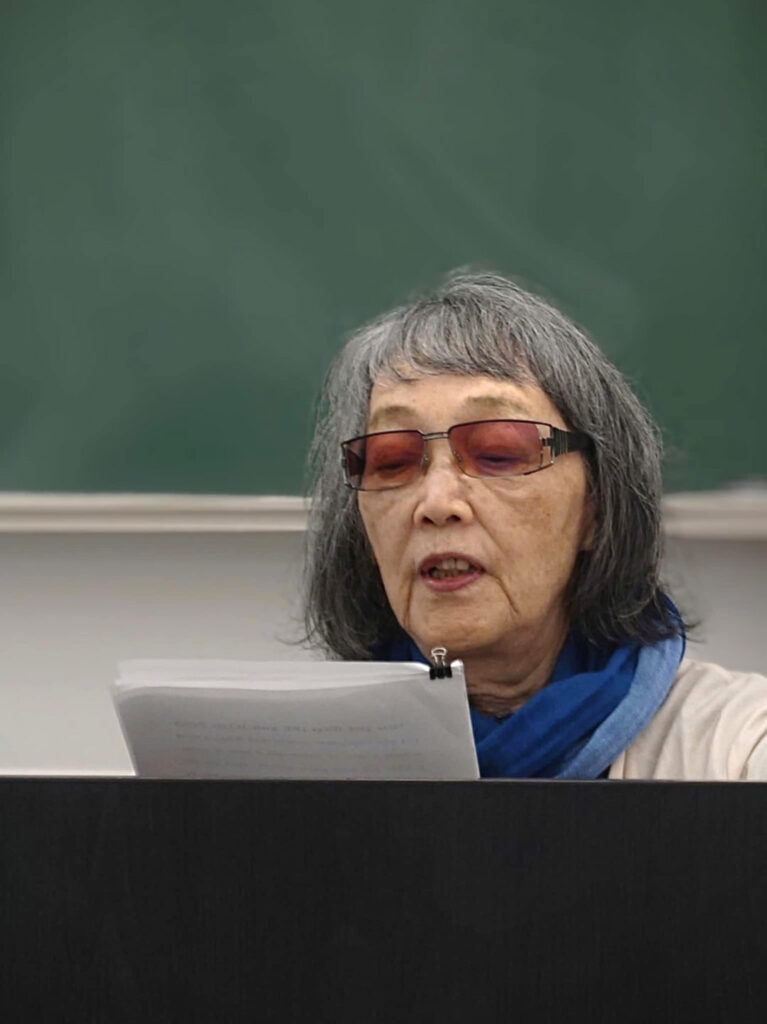

Yoko Danno the founder of Ikuta Press, which published Hubbell’s work after he came to Japan, was greatly encouraged by Hubbell at the start of her own career as a poet. She shared some amusing recollections of him, including her first meeting with him in 1967, at his house in Kyoto. Her anxiety at meeting the famous professor was soon dispelled by his playful yakuza-style greeting when he opened the front door and his admission that, because his house had no bath, he had taken up the offer of the proprietress of a nearby “lovers’ inn”, who had said he could use her hot spring facilities to take a bath after midnight. He did this before his usual bedtime of 4.00 or 5.00 a.m.

Rossiter followed this with readings of Hubbell’s poems, moving from the early, short and formal rhyming verses in the style of the New York poets of the 1920s, through the greatly expanded range of the work of his mid-thirties that followed a time of personal crisis. It was during this period that he produced the modernist “Long Island Triptych”, which Rossiter considers to be a masterpiece and one of the few cubist poems in the English language. Hubbell moved to Japan in 1953, at the age of 52, after which his poems became more relaxed and often humorous, though still technically precise:

KAMAKURA (1967)

After fourteen years the loudspeaker blaring jazz had gone.

The bars and the soft drink stalls had gone with time.

The G.I. whores who climbed on the statue to be photographed

Were superseded by a sign that said: DO NOT CLIMB

ON THE STATUE. Japan had reasserted itself.

Reverence had returned to the place.

But to the Buddha it was as if nothing had happened.

There was no change in his face.

Hubbell, who lived to the age of 93, spent the last few years of his life bedridden in a hospital ward that he had to share with some other elderly patients — the only lucid mind in a roomful of senility. A private room in a Christian hospital was procured for him, but he refused to move into it, saying he was dedicated to Shinto, not Christianity.

Paul Snowden, who met Hubbell in 1969 through his wife who was a student of Hubbell’s at Doshisha University, was also moved to come forward and share some stories about him. He recalled visiting him at his small house in Nishinomiya, near the Hanshin baseball stadium, and said that he was charming and generous, sending the Snowdens, from that time onwards, a copy of every volume of verse he had published.

After the readings we looked through the wide selection of Isobar Press publications at temptingly reduced prices which Rossiter and his wife had brought with them, and the Ikuta Press pamphlets that Yoko Danno had brought with her to give away.

Some of us then headed to a nearby Italian restaurant where Paul told us a lot more about his experiences with publishing.

Walking back to Kyoto station after dinner, with others who had come from faraway locations such as Kobe and Gifu, with a stomach full of beer and pizza and a backpack full of new books, I felt that it had been in many ways a very nourishing day.