Mike grew up in San Francisco, and attended USF as an undergraduate before earning his PhD in Artificial Intelligence at MIT. While there, he helped co-found MIT’s literary magazine Rune and studied poetry under David Ferry at Wellesley. In 1977, he was named a Luce Scholar with an appointment to Kyoto University. Mike and his wife translated They Never Asked, a collection of senryu poetry written by Japanese-Americans incarcerated during World War II, which was a finalist for the Washington State Book Award in 2023. Mike’s most recent book is a translation of the Hyakunin Isshu, published by Tuttle. Mike has been an active member of Writers in Kyoto for some years.

A New Year’s holiday evening in the 90s, and in our home, a Hyakunin Isshu tournament is in progress. The drone of my mother-in-law reading the poems and repeating the all-important last two lines; the silence as the card is searched for; the slap of the card as it is taken from the floor; the barks of triumph and the moans of defeat. I listen to the familiar sounds from the kitchen where I am washing dishes. My upper-elementary-school-age son, who is in the card team currently being coached by a local priest, is involved in the game. This traditional New Year pastime, called One Hundred Poems in Japanese, involves, to win the game, taking more cards with the last two lines of the poem printed on them than your opponent. The poems are in the traditional waka format, 5-7-5-7-7 syllables per poem. To be really skillful means memorizing the first half of the poem so that you can find the card with the last two lines quickly. In our house, the “answer” cards are splayed as for the card game “Concentration,” but in a real game between experts, such as one sees on TV at this time, they are lined up between the two contestants, who sit facing each other. It’s really a two-person game, but anyone can join in, the way we play. I used to try, but it is really too hard for me to read the archaic hiragana script of the cards, so I mostly just listen.

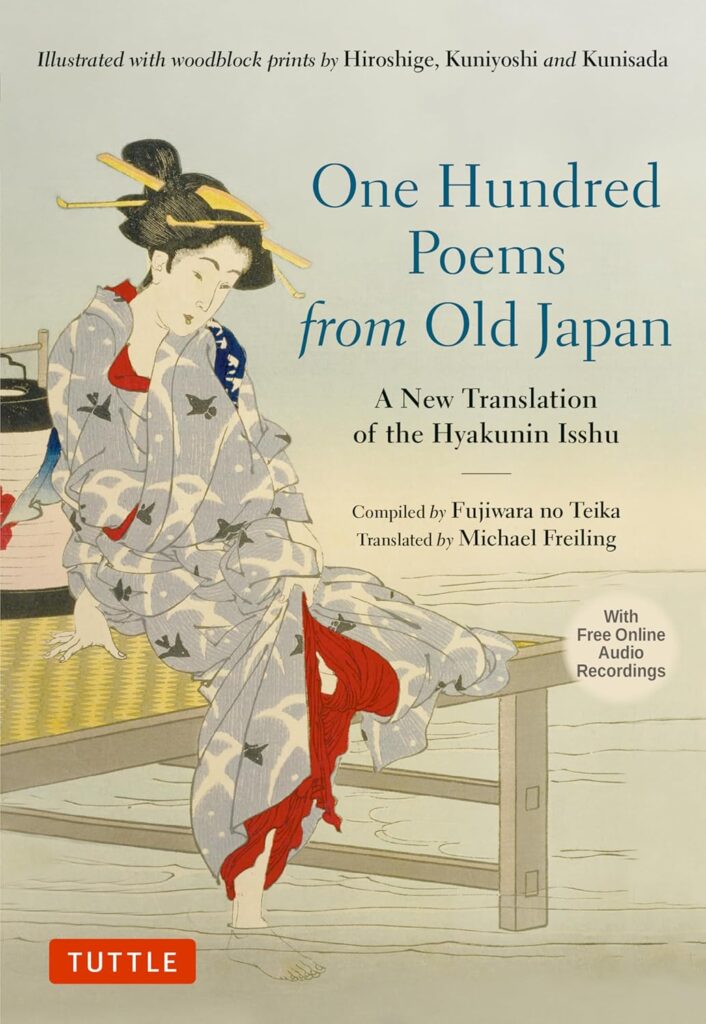

One Hundred Poems from Old Japan would be a welcome addition to any Japanophile’s bookshelf. Handsomely illustrated with Edo-period woodblock prints specially commissioned from artistic masters Hiroshige, Kuniyoshi and Kunisada, each opened page consists of an illustration, the number of the poem, the author and sometimes court title (from the Emperor’s court during the Heian period, around the tenth century), the English translation, the Japanese original, and the romaji (alphabetic rendering) of this last, arranged beautifully over the space.

Michael Freiling came to Kyoto in his youth, and his big project as a Henry Luce scholar in 1977 at Kyoto University was translating the One Hundred Poems into English, several of which graced the pages of the 4th Anthology of Writers in Kyoto, Structures in Kyoto. As one of the co-editors of that anthology I was glad to see his translations of other poems as well, the complete work in fact, in this book. I knew that these poems can be read on many levels, and it was interesting to see how the translation, in many cases, included nods to these various levels. For example, my favorite of the collection, No. 66, ends with the lines, hana yori hoka ni / shiru hito mo nashi (“No one sees the blooming of the mountain cherry except the flowers themselves”), which is one level, that of a natural scene; another is a lament by the author, the former Archbishop Gyoson, for his loss of status; as translated by Freiling, “…for both of us [me and the blossoms]/ no other friends are left.” It is true that these levels of meaning have not been, by and large, arrived at by asking the poets themselves, but by inference through information about their lives and preoccupations provided by their friends, later commentators, etc. But it is interesting to be aware of them. The levels are arrived at naturally using poetic words and images which have more than one meaning in this poetic framework. It would be interesting and educational to see translations of the poems from the viewpoints of some of these several levels in the same place, for comparison purposes.

The Introduction, which is fascinating, covers such themes as “Court Life in the Heian Period,” “The Merry-go-Round of Love,” and a very interesting portion which lists localities in modern Kyoto which are associated with the poems, “Modern Kyoto and the Hyakunin Isshu,” as well as short biographical notes about some of the more well-known poets featured in this collection. The Ogura Hyakunin Isshu collection was originally made by Fujiwara no Teika, a member of the very important court family Fujiwara. Works of several members of this family, who were poets as well as public figures at that time, can be found in the collection, including a poem by the compiler himself, No. 97. It is to be noted that many of the included poems were written by women, including Sei Shonagon and Lady Murasaki, women being a very important part of the literary and cultural life of the Heian court. Lady Murasaki Shikibu, particularly, is famed for writing the novel The Tale of Genji, which sheds much light on the court as it was at the time of these poems.

The illustrations are full of life and wonderful in design, which one would expect from such experts in the field of woodblock printing and artistry. I confess that I was a bit confused at first by the juxtaposition of the illustrations and the poems – “what are they supposed to be illustrating anyway?” I thought. I should have read the Introduction first, which states, in the words of the author/translator, “The … illustrations… are from the series The Ogura Imitations of One Hundred Poems by One Hundred Poets (Ogura nazorae Hyakunin Isshu)… The print series was made specially to illustrate this volume of poems, and the imagery in each print is based on scenes from Kabuki theatre that relate to the theme of each poem.” Thus the illustrations, although all showing human beings, are not of the poets themselves (this was the initial source of my confusion), and sometimes the theme connecting the picture to the poem is rather difficult to grasp for a modern reader, but those that, for example, include the moon (No. 59), maple leaves (No. 24) or snow (No. 15), are self-explanatory. (The compendium of illustrations is described as “playful” by one Google commentator, not particularly serious that is, but one would have to be conversant with a lot of literature and literary figures to feel the playfulness.) It would be nice to know which Kabuki play and which scene are being referenced, but such information is not within the scope of this book. One also must keep in mind the discrepancy in period between the poems (around tenth century) and the illustrations (around eighteenth century). Still, the illustrations are impressive, and beautifully rendered.

This edition includes a link to free audio recordings of the poems at the end of the Introduction.